If you were to ask almost anyone if they could see a link between the speed of 5G cellular connections and airplane safety, you’d be hard pressed to get a response. And yet, because of a surprising and sudden request from the Federal Aviation Administration that’s based on unverified potential radio interference, a highly anticipated increase in 5G speeds and availability just got put on hold.

Before we get into the explanation of why, a bit of background is in order.

At its heart, it is important to remember that 5G – like all cellular networks – uses radio waves to operate. Signals are sent from our smartphones and received back from cell towers at particular frequencies. Think of it like an AM/FM radio. By tuning to certain frequencies, you pick up particular stations and not others.

► Talking Tech newsletter: Sign up for our guide to the week’s biggest tech news

In addition, the quality of that signal (and even what station a particular frequency may be linked to) depends on your location. In other words, 93.1 on your FM dial in Chicago isn’t going to give you the same station (or perhaps any station) if your car happens to be in Lexington, Kentucky.

Similarly, the types of signals you can receive on a 5G smartphone (and the quality of that connection, measured in bars on your phone’s display) are highly dependent on the frequencies that carriers like AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon broadcast in any given location. The speed of the connection is related to how wide the groups of frequencies that 5G (or 4G) signals are being sent on.

Unlike most radio stations, cell signals aren’t limited to a specific frequency but can be simultaneous sent across a whole range of frequencies. Think of this as the width of the digital superhighway: the wider the road or, in this case, the wider the block of frequencies being used, the more data that can be sent at once. And the more data you send at once, the faster the connection.

► iPhone issues: Apple pushes update related to iPhone 13 screen repairs

Which wireless carriers are affected?

The reason all of this matters is because one of the most exciting aspects of 5G is that it’s supposed to use new frequencies to send its signals and wider blocks of those frequencies to send data at faster speeds.

In fact, much of the promise of 5G has been based on this expectation. Unfortunately, as many consumers have already discovered (particularly those using AT&T or Verizon), that promise has yet to be fulfilled because 5G has made little to no impact so far in the smartphone experience and download speeds of most users.

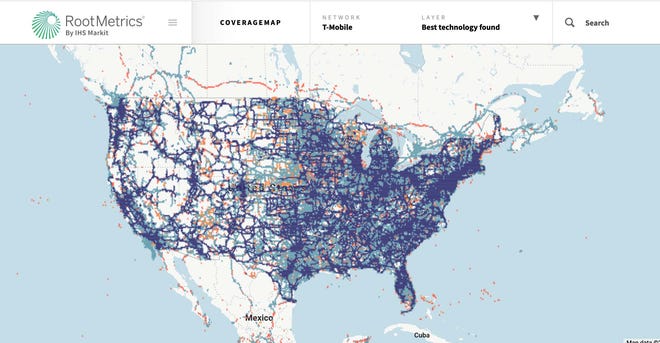

T-Mobile has been able to leverage some large chunks of frequencies it gained access to when it purchased Sprint in 2019, hence, their current lead in most 5G speed tests.

► Which wireless carrier has the best coverage where you’re going? Here’s how to find out

The 5G situation was set to improve for all consumers starting Dec. 5. That’s when the most highly-awaited block of new frequencies for 5G services was scheduled to go into regular use in the U.S. starting on Dec. 5 by both AT&T and Verizon. Generically referred as C-Band, these new 5G frequencies range from roughly 3.7 to 4.2 GHz on what’s known as the radio frequency (RF) spectrum.

FAA: New 5G frequencies are too close to ones used by radio altimeters

At the last minute, however, the FAA jumped in, citing potential conflicts and interference with radio altimeters, cockpit instruments which tell pilots how close a plane is to the ground as it comes in for a landing. The issue boils down to the fact that radio altimeters use frequencies from 4.2 to 4.4 GHz in their operation.

With those two groups of frequencies located so close together, the FAA argues, 5G cell signals using C-Band frequencies might interfere withradio altimeters. And because this potentially involves the safe operation of planes, it’s easy to see why concerns might be raised – at least, initially.

But as soon as you start to dig into the details, the concerns quickly seem less practical and more political. Most notably, the plan to launch 5G services on C-Band frequencies has been in the works for several years and really took on momentum after the three big U.S. carriers spent over $80 billion earlier this year to get access to these frequencies.

In addition, a report that the FAA cited as part of their complaint has been out for well over a year, so why the last-minute concerns?

Inter-agency beefs to blame?

U.S. government agencies are, unfortunately, known to hold grudges against one another, sometimes without real clarity as to what’s actually involved, as appears to be the case here.

The bottom line is that a questionable objection from the FAA could end up delaying the rollout of a critical new technology enabled by the Federal Communications Commission to a broad swath of the U.S. public.

Delayed progress

Along the way, it could also delay important (and significant) economic impacts that virtually everyone expects to come from the wide availability and use of truly differentiated 5G service.

Every previous cellular generation change has triggered billions of dollars of new business and thousands of new jobs by creating new opportunities that faster wireless networks bring with them and 5G is expected do the same. On a practical level, stronger 5G networks and wider availability can also inspire stronger sales of 5G phones (and the components that power the

m), the faster build-out of 5G networks (and all the equipment required to enable them), and new services that carriers can offer, including things like wireless broadband services using cellular networks (a topic also called Fixed Wireless Access, or FWA).

Along the way, it could also delay important (and significant) economic impacts that virtually everyone expects to come from the wide availability and use of truly differentiated 5G service.

A 400 MHz buffer zone

The initial deployment of C-Band here in the U.S. is only going to use frequencies from 3.7 to 3.8 GHz – what’s called the A Block. That leaves an enormous 400 MHz gap between the initial C-Band-based 5G services and the radio altimeter usage.

The B Block, which includes frequencies from 3.8 to 3.98 GHz, isn’t expected to be put into use in the U.S. until 2023. And once they are, that still leaves a 20 MHz “guard band” between the top of the B Block and 4 GHz.

On top of that, frequencies between 4.0-4.2 were intentionally withheld from 5G services and will continue to be used by large C-Band satellite dishes (which, for the last several decades, used to leverage the entire C-Band block), for things like remote TV broadcasts, etc.

To put this into context, it’s important to note that the usage of specific RF frequencies is tightly managed by agencies like theFCC to ensure that numerous applications can coexist and regular changes to these frequency blocks for different applications happen all the time. Many of these blocks are contiguous and often as small as 5 MHz wide, so the 400 MHz gap between the planned 5G service and radio altimeters really is huge from an RF perspective.

U.S. falling behind on 5G

Some 40 countries around the world are already using most of the C-Band frequencies for 5G (part of the reason the U.S. has fallen behind on the 5G front), and none have reported any interference with radio altimeters on planes in their countries, the wireless trade association CTIA argues on its website 5GandAviation.com.

In addition, new filtering technologies being built into a somewhat obscure part of smartphones called the RF (radio frequency) front end, such as Qualcomm’s recently introduced ultraBAW filters, can reduce interference issues on next generation smartphones.

All told, there are numerous reasons why the FAA’s concerns around 5G deployment look to be more of a red herring than a legitimate technical concern. While it is true that some older radio altimeters with poor filtering might have to be updated and/or replaced to completely prevent interference, it’s not clear that the theoretical interference would even cause an issue.

While airplane safety shouldn’t be compromised in any way, an overabundance of unnecessary caution on this issue could have a much bigger negative impact on the U.S.’s technology advancements and economy than many realize.